Dear visitor,

Obviously, you have landed on the test site of our new project Language and Science!

We will soon take off – in the meantime check us out on our up-and-running Hungarian site: www.nyest.hu.

If you do not speak Hungarian... well.. you just go on and use Google Translate.

And if you have a comment or a suggestion, drop us a line!

When watching a newborn baby’s first instinctive exploration of the world around him or her, have you ever thought to wonder how an infant’s inarticulate vocalizations turn into real language in a very short time? That’s the question we’d like to explore in this article, which is really a quest for the origins of linguistic ability.

The boffins in our world are nowhere near to agreeing on how children learn to speak. In fact, the psychologists, linguists and philosophers have come up with two diametrically opposed theories. One group says it’s all in our genes, while the other gives genetic theory a thumbs down, and says it’s all learned.

(Source: (Source: Krisztina Fehér))

At one end of the scale we have American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist etc., etc. Noam Chomsky, and his theory of innatism. Chomsky argues that not only are we biologically programmed with the general ability to learn our native language, but that we also inherently carry all the algebraic formulae that make up all possible linguistic structures – or in normal English, Chomsky says that all the rules of grammar and sentence structure for every language ever invented are biologically encoded into our brains. To activate that genetically pre-programmed information and turn it into an actual language, whatever our native language may be, all we need is to be born and start the hearing experience.

At the other end of the scale are the theoreticians who argue that nothing is innate. At birth the brain is a “tabula rasa” or blank slate, they tell us. The blank slate supporters argue that everything we know has to be learned and that we begin the learning process at birth.

You might have noticed that the two theories have exactly one point in common: Birth. Both think birth is a crucial marker although they approach even the birth moment from opposite ends of the scale. For the innatists, every significant component of language has been planted in the brain by genes and birth only starts the demonstration of the innate skills, while for the tabula rasa group birth is the true starting point of skills acquisition. So, who’s right and who’s wrong? Too bad we can’t ask the babies…. Or can we?

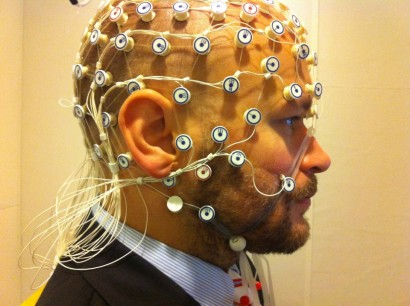

(Source: (Source: Wikimedia Commons / Pospiech / CC BY-SA 3.0))

Luckily, we also have cognitive specialists whose job it is to come up with ways to learn things first hand, especially when asking questions doesn’t work. And our cognitions have really come up with methods to get newborn babies to answer questions on linguistics. Since newborn babies are definitely pre-verbal, meaning that they can’t talk, these boffins have designed experiments in which instruments measure behaviours and responses to certain stimuli. They collect information on language and language development by carefully observing those behaviours.

The talking dummy …

One type of test the cognitive scientists swear by is the teething dummy. Based on the observation that when a neonate or young infant encounters an unfamiliar and interesting stimulus his or her sucking frequency and intensity will increase, a neonate is given a dummy to suck on. By playing sounds and measuring sucks per minute science can learn whether an infant can distinguish between two different types of sound, in this case language stimuli, and if they can, will they pay more attention to one language or the other.

If the infant is mouthing a dummy with a sensor attached during these experiments measuring the sucking tempo is a simple matter. So, with a sensor attached to the dummy, scientists started playing recordings of the two stimuli one after the other in a smooth and uninterrupted sequence. When the baby heard the first tones of Text One, sucking frequency increased but as he or she became used to the sounds the frequency gradually dropped to a lower level and stayed low until something new (to the baby) came along.

In other words, when the scientists switched from one language to another in a completely smooth change-over the babies could have responded in either of two ways. If they did not notice any difference between the two texts, their sucking frequency would be expected to remain unchanged or keep going downward. But, if they did notice a difference a sudden increase in sucking frequency would signify it. If they perceived a difference, the different sucking frequencies on hearing the alternating texts should tell us if they “liked” one of them more than the other.

(Source: (Source: Wikimedia Commons / Jirkasirka14))

… or Granny’s hairnet

The sensor-equipped dummy isn’t the only way to learn about infants and language. We can use other tools to map out the ways their nervous systems operate.

The tools used most often on adults, functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) or Positron Emission Tomography (the PET scan) cannot be used for babies. There are both ethical and practical reasons for this. One the one hand, we simply do not know whether the powerful magnetic field and/or the isotopes are safe for young children. In addition, the fMRI is noisy and the PET scan requires giving an injection, meaning that we would have no way of knowing whether the babies’ responses were due to recognition of something or to the unusual (for them) test conditions.

However, an electroencephalograph (EEG) can work rather well. The EEG calls for placing a series of tiny electrodes all over a person’s head and measuring the mass of electronic discharge by the brain’s nerve cells. Wearing the electrodes does not bother a small baby so it is not a distraction. The electrodes are built into a cap that resembles the hairnets our grannies used to wear. They contain either 64 or 128 electrodes wrapped in soft sponges, and slipping the net onto a baby’s head takes just a couple of minutes.

(Source: (Source: Wikimedia Commons / Petter Kallioinen / CC BY-SA 3.0))

And guess what! Whether tested with the dummy or EEG cap, the outcome was the same, with the babies showing a clear preference for their own language, at least over other languages which differed in rhythm and tonality from theirs. And yes, they showed this marked preference at birth!

Tonality in the crying of a neonate!

The linguists have just dropped another bombshell on us. A recent study has suggested that a newborn baby can not only hear his or her native language at birth, but can “speak” it, too. Researchers ran computerized analyses of the cries of three-to-five-day-old infants and found that the wails of German neonates tended to begin on a higher note with the greatest intensity at the beginning while French neonates started their wails on a low note and built to a higher intensity. In other words they were displaying the tonality and accentuation of their own languages in their very first cries.

Born linguists or just hard workers?

While the general public may be astonished by these findings, the professional world is embarrassed. The “blank slate” crowd has clearly been swept away. The experiments show us that those slates are anything but blank! They definitely contain language information. But the innatists are also shaking their heads. Their theory of a biologically programmed equal potential for all languages has been booted out by the clear preference the babies show for the tones and accents of their own native language.

While we are obviously not going to resolve all the secrets of linguistic ability today, it does seem most probable that the real answer(s) is(are) somewhere in the middle. It does appear that we do carry the genetic ability to recognize language (albeit not the “algebraic formulae” for the rules of grammar) and this eases us into our native language, but that language still has to be learned. In other words, we are both born linguists and hard workers.

That, of course, only holds true if we abandon birth as the demarcation line between knowing and not knowing. These experiments strongly suggest that the learning process does not begin at birth but merely continues. But where could a neonate have learned anything about language … except in Mommy’s tummy.

Foetal language study

It’s noisy in that womb! Noises from the outside world pass through the mother’s body and cause the amniotic fluid to vibrate, tickling the eardrums and other hearing organs of the foetus, whose ears become functional at around the 20th week of pregnancy. Studies of pre-term babies have demonstrated that audio-stimuli trigger responses in the cerebral cortex at around the 30-32nd gestation week, and from 26 weeks onward foetuses will move their bodies in response to sound. Soon afterward, their hearts rates speed up in response to outside noise.

(Source: (Source: Wikimedia Commons / Staecker))

So, not only do foetuses hear the sounds of language coming from the outside world, they also apparently learn from them. Many tests of neonates that measured sucking frequency have demonstrated that not only had they learned to recognize their mother’s voice before they were born but also picked up other sound patterns which they “memorized.” Neonates showed a clear preference for their mother’s speaking voice over the voices of other women, but also preferred nursery rhymes and songs that they regularly heard during the last six weeks of pregnancy, even if the presenting voice was not their mother’s.

They have not actually learned the rhymes in the way they learn them later, in pre-school or school. What they have picked up is not the concrete text, but the rhythms, accentuation and tonality. And this coincides with the finding that a newborn infant is only able to distinguish his or her native language from other languages if the other languages differ in rhythm, tone and accentuation.

This should not surprise anyone, for the amniotic fluid surrounding the unborn baby is a filter that does not allow all acoustic nuances to get through. To use an inaccurate but nonetheless illustrative comparison, the foetus picks up about the same quality of sound from the outer world as does a swimmer during an underwater dive. The swimmer will hear speech rhythms, accents and tones if the dive isn’t too deep, but will not be able to pick out exactly what was said.

Actually learning all those words and what they mean is a huge task that gets underway after the baby is born.